Beginning of the story

The whole story of the Berger cave begins here, behind the porch of the Cuves de Sassenage, whose mystery has always aroused curiosity over the centuries.

This cave is considered one of the seven wonders of the Dauphiné.

From its porch flows a river, the Germe, whose origin was unknown.

Where does this river that rises from the mountain come from?

In 1947, a group of young Grenoble residents, some of them teenagers, attracted by the caves (Joseph Berger, Louis Eymas, Jean-Jacques Franchini, Géo Mathieu), without any method or equipment, set out to explore them in secret, using flashlights.

The course of their explorations was to change on 27th October, when one of them, Louis Eymas, stumbled into an unsuspected hole leading in the Stix room.

This bypassed the large scree slope that blocked the room and gave access to the unknown continuation of the Cuves de Sassenage.

This lucky find of such a key passage will be the subject of future explorations.

The new area proves to be vast and varied, raising hopes of a great continuation to be discovered.

They meet a more experienced group called “les Fadas” (Marius Gontard, Roger Michallet, Maurice Caille). Together, they join forces to explore this new and sometimes tricky system.

The discovery of new rooms follows (Halls of the giants, dining room, Cairn room with several gallery departures, including the western one).

They soon met up with other enthusiasts, and the team was strengthened by the addition of new members, some of them more experienced (Jean Cadoux, Jean Lavigne, Aldo Sillanoli, Charles Petit-Didier, Pierre Chevalier and Fernand Petzl).

The search continued with the discovery of a new passage at the bottom of the Lavigne shaft, giving access to the rest of the network to the west, towards the Saint Nizier plateau. However, in 1950, a sump at the end of the Cuves was discovered.

In just a few years, the network had grown from 200 to 1170 meters. Stuck, a little discouraged but not resigned, they looked elsewhere

The beginning of 1951 was devoted to a number of unsuccessful prospecting trips on the St Nizier plateau, where it seemed logical to look, and in the Engins gorges, with no results.

Given the geological features, and the orientation of the terminal sump, we turn our attention to the Sornin plateau.

The area to be explored is immense, covering several thousand hectares at an altitude of between 1000 and 1600 metres, and consisting of an immense Lapiaz (limestone plateau eroded by water run-off).

There is no access road, and it can only be reached via the village of Engins after a 2h30 walk, not counting the climb from Grenoble, which is often done on foot, by bike or by bus.

They prospect and search using aerial photos in particular .

In July 1951, the Grenoble team, in collaboration with the Spéléo club de Lyon who supplied the equipment, discovered a shaft to the north of the refuges (christened P2).

They stopped at -260m and the shaft was finally abandoned after several explorations.

However, it will serve as a lesson following a violent storm and a disaster narrowly averted. Aldo was almost swept away by the waterfall and probably fell, due to a lack of communication. For the rest of the explorations, which will take several days, they will install the telephone.

Encouraged by this result, they concentrated their research on this sector. Georges Marry (speleologist/director), Paul Brunel and Louis Potié (in ’51) then Pierre Lafont, Pierre Breyton and Jacques Berthezebe (in ’52) complete the group.

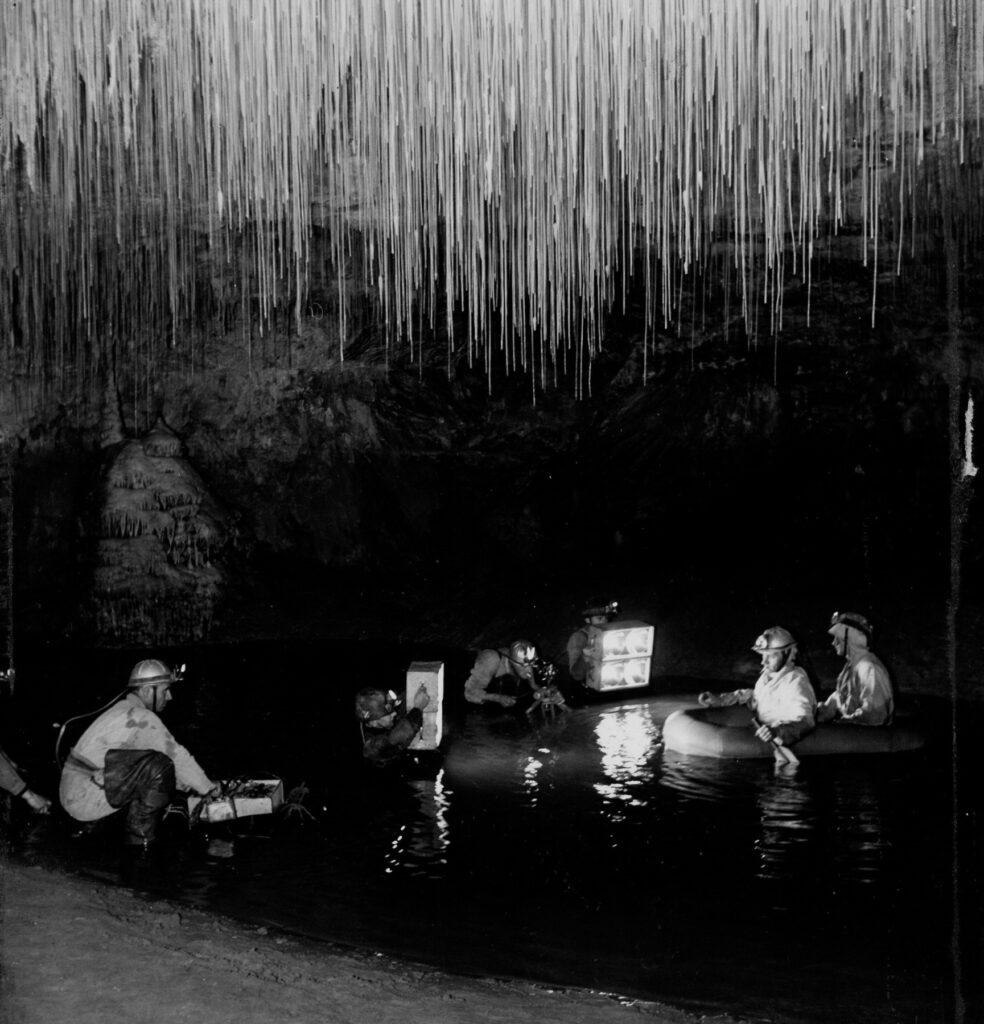

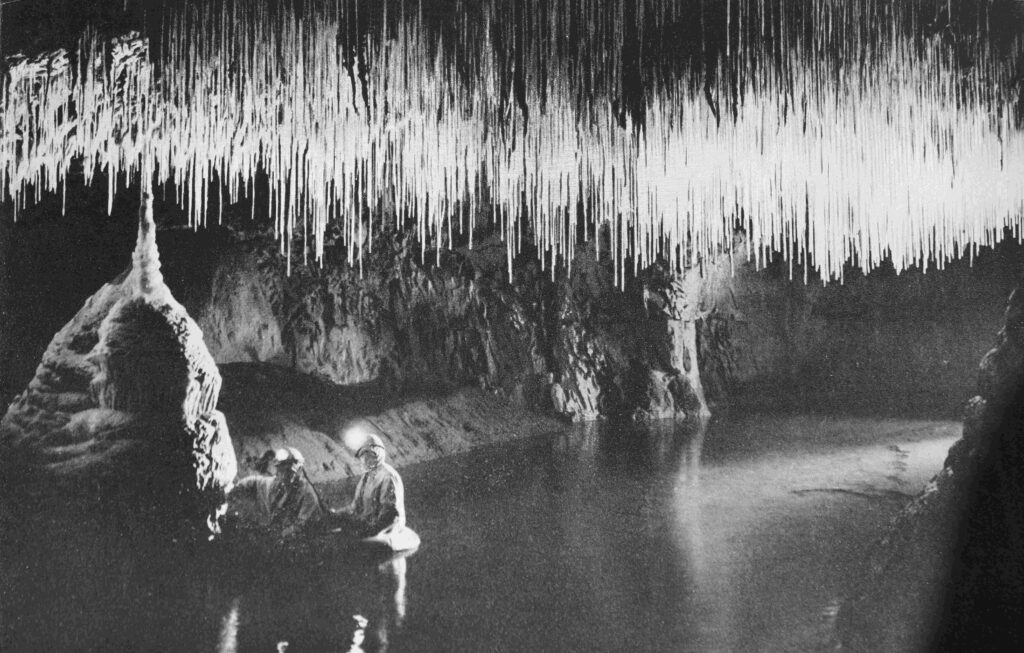

In 1952, under the impetus of Georges Marry, the team embarked on the production of a colour film about the underground world, “Rivière sans étoiles”.

It will share the mysteries of this strange world with as many people as possible. Much of the filming will take place in the Choranche, Couffin and Gournier caves, with their hundreds of thousands of fistulas

This “interlude” was to prove extremely useful, with the development of a lighting system for filming underground, using truck batteries and a small generator to recharge on site. The equipment is heavy and cumbersome, and not always easy to hoist into the caves.

It took the team no less than forty sessions to shoot the film.

They will spend many weekends heavily involved in the making of this film.

It will have the advantage of further strengthening the group’s solidarity and friendship, reinforced by the shooting sessions.

All in all, the period from 1947 to 1952 saw the building of a united team.

It built confidence and gave them a professional experience with very complementary personalities, without any particular leader, ready for the future challenge that awaited them.

… of which they were not yet aware.

The film is a great success.

In 1953, it won 1st prize for mountain film and best colour film at the Trento Film Festival in Italy.

This will be followed by a roadshow across France.

Anecdote : Not the day !

During an exploration in 1951, it was raining outside. Some were at -120m when, in 10 seconds, water came rushing in at high speed, showering Aldo and Mathieu.

Petzl, who was belaying Mathieu, while belaying one, threw the other end to Aldo, who was suffocating, had no light, and who, as he would later say, believed his last hour had come. By a stroke of luck, Aldo was able to make out the rope through the curtain of water from the waterfall, which had fallen onto a rung of the ladder.

Photos : Collection Jean Lavigne, Jo Berger, Georges Marry