1953 Discovery

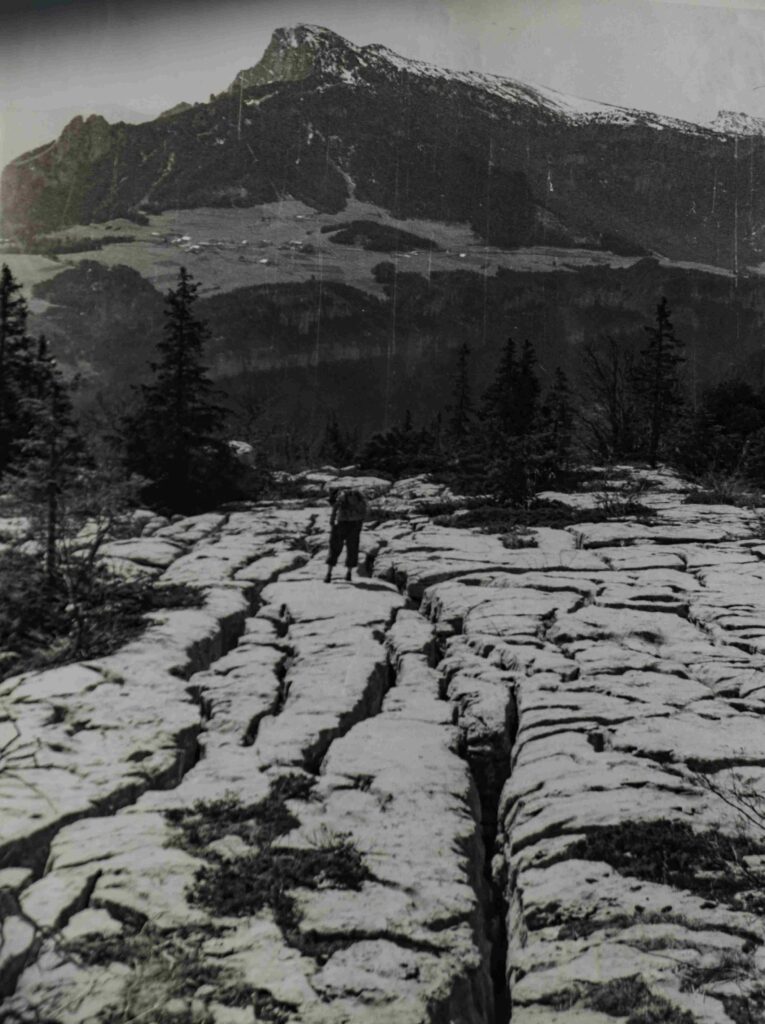

After the production and release of their film “Rivière sans étoile”, the outings continued in April and May 1953, on the Sornin plateau, concentrating on the Sure area. In all, no fewer than fifty shafts were descended, ranging from 20 to 100 meters.

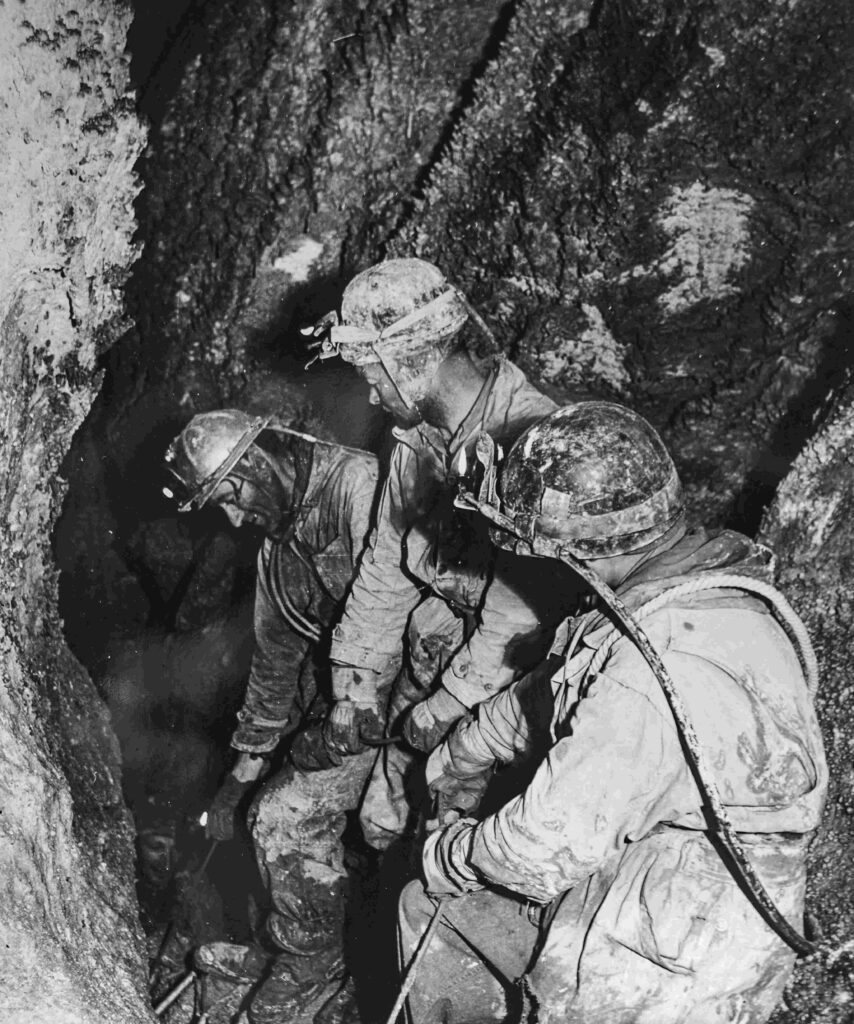

It’s important to point here out that the technical resources of the time were still quite limited.

The first ropes were made of hemp (weighed down by water during ascents) and a few nylon ropes of varying elasticity. Flexible metal ladders were made and paid for themselves, sometimes from ski pole off-cuts (linked together with carabiners). Helmets are fitted with acetylene lamps (or carbide lamps), and wetsuits quickly soak up water.

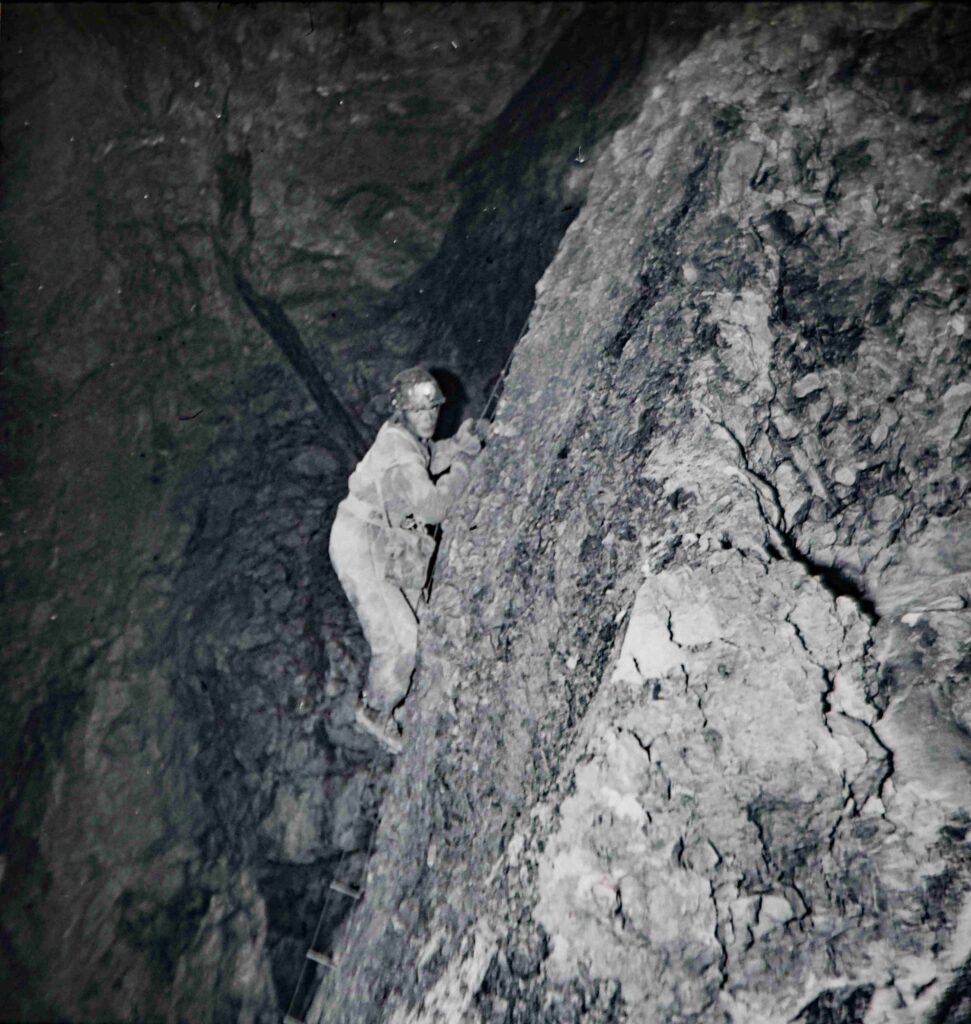

Descents are made by abseiling (on a rope ring or with a carabiner) and ascents by ladder. Pitons are fixed in the cracks with han drills, molten lead and bolts.

On 24th May, Jo Berger was lucky enough to discover the first entrance to the cave (named P3 and then Gouffre de la Rivière) with his companions.

Jo throws a ladder down and descends. He’s pleasantly surprised to find a crack at the base of the shaft, which leads to the top of another large shaft. The others joined him, then descended the entrance shaft and the Ruiz shaft (when exploring for the first time, pitches are usually named after friends, acquaintances… or just with imagination) and reached -52 meters. They stop for lack of ladders.

On 25th May, the same team descended to the bottom of the Cairn shaft (-103m), but one of them (Ruiz) fell 16 m, without too much harm.) the ladder having broken. The exploration stops there, for lack of equipment, but they come back up enthusiastically.

The 14th July, with its bank holiday, was quickly chosen as the date for the next expedition. However, they needed to gather sufficient equipment, as they could no longer count on the Lyon team. Claude Arnaud (Spéléo club de Genève) and Georges Garby (Spéléo club de Dijon) answered the call and joined the group with additional equipment.

On 13th and 14th July, 1953, they hauled 300 meters of ladder and almost 400 meters of rope up the shaft. A team of 10 cavers (Claude Arnaud, Georges Mary, Jo Berger, Jean Lavigne, Paul Brunel, Louis Potié, Aldo Sillanoli, Marius Gontard, Georges Garby, Jean Cadoux) descended a series of shafts with a total vertical length of over 220 meters, leaving a team member at each pitch head.

The shafts are intersected by long meanders (tortuous, narrow galleries several tens of metres deep), which are very tiring to cross, often requiring bridging over their length, sometimes for more than 100 metres.

At the bottom of the last shaft, Georges Garby and Jean Cadoux set off as a team, hearing the sound of water at the exit of one of the meanders through a small window. They emerged into a huge gallery 80m high and 20m wide, where the starless river of their dream was flowing.

The river in their film has become reality!

They travel through this vast gallery with its 40m-high ceiling, skirting the river as it meanders between sandy beaches and gigantic boulders that have fallen from the ceiling.

Progress is soon halted, as the river’s waters are held back by a natural dam that occupies the entire width.

This lake (Cadoux Lake) they won’t be able to cross. They didn’t think to bring a boat!

That day, the -300m level was reached with 824 m of horizontal development.

They return in November with a rubber dinghy to cross the lake and reach the top of a huge 40-50 m-high hall (named after André Bourgin).

The hall features large, strangely-shaped concretions (stalactites, stalagmites and draperies) and crystal gours.

On 26th October 1953, Charles Petit-Didier, who had left the group in ’52 (later nicknamed the Petit Général), accompanied by members of the Lyon Alpine Caving Club, crossed Lac Cadoux and reached the 10m waterfall that bears his name.

He pours in 36 litres of 50% fluorescein. The coloring came out 48 hours later at the Cuves de Sassenage, much to the surprise of the villagers. It should be noted that it was also seen 2 days later in the Gorges de la Bourne, confirming a geologically complex underground route.

This pirate trip resulted in an “explanation” to exit of the cave. The cave was definitively named “Gouffre Berger” by the people of Grenoble. The Mayor of Engins, Mr. Charvet, also took step to ensure the organisation of expeditions of the Berger cave were reserved for the Grenoble discoverers, which was only fair.

The year 1953 came to a close between the 7th and 9th November 1953, when a team reached “la Tyrolienne”, a depth of -372 m, with a more than promising follow-up …. to their great delight.

Anecdote: A little too short!

Garby and Cadoux went down the shafts first, as they were the topographers, with the others taking turns at the top. In 1953, descents and ascents were made using ladders, and Gabry was the first to launch himself down the Aldo shaft. He launched a 10 m ladder, but when he reached the end he realized he needed more. Fortunately, Cadoux had just joined Aldo at the top of the shaft, and sent a 40 m. ladder train, which Garby was able to connect to the 42 m. long shaft.

Series of Georges Marry’s short films on research and discoveries from 1952 onwards.

Photos : Collection Jean Lavigne, Jo Berger, Georges Marry