1954 World record

At the beginning of 1954, the team planned for a larger expedition during the summer, requiring 3 months of preparation. The sheer size of the cave called for new methods. Carrying the equipment made progress through the shafts and meanders difficult and tiring.

So they needed to consider a different mode of exploration, rather like a high-altitude mountaineering.

They decided to set up fixed base camps with tents to bivouac as deep as possible in the cave system, and to manage these with a support team and a top surface team. This time, they planned to go down in rubber dinghies and equip themselves with wetsuits. Given their means, they are appealing to a number of companies for food supplies. The rest is financed by them.

They will also take a number of scientific measurements and samples (temperature, hydrometric flow, Ph, cave insect collection).

Last but not least, most underground accidents are due to a lack of communication with the outside world (as we experienced when exploring the P2 in ’51). Maintaining a link with the surface is vital if we are to avoid finding ourselves in parts likely to flood when weather conditions deteriorate.

At the beginning of July 1954, a ton of material had to be hauled up from Engins on men’s backs to rig the cave. After several preliminary descents, carrying 48 bags to the Bourgin room and setting up a telephone link with a 1st station at -250m, the expedition could properly begin.

On 24th July, they’re off for a week underground.

Surface support is provided by Georges Marry, Marius Gontard,Roger Michallet, Marc Soulas, Jacques Berthezène, Robert Juge, Pierre Laffont, Pierre Breyton, Gérard Peaudecerf, Abelle Lavigne, Claudine Lecomte, et Mme Gontard.

The top team of 13 cavers (G. Garby, J. Cadoux, P. Chevalier, J. Berger, J. Lavigne, C. Arnaud, L. Potié, A. Sillanoli, F. Petzl, P. de Brétizel, P. Brunel, L. Eymas, G. Mathieu) pass the Tyrolienne.

Ahead lay the unknown. They descend an immense gallery with a rocky chaos (the Grand Eboulis) with highly unstable blocks whose walls remain invisible due to their lighting.

The team reaches a magnificent chamber at -500m, adorned with splendid columns, curtains and gour pools. This room was to become known as the Salle des Treize. The team sets up camp here, which becomes Camp 1.

On 25th July, they descend the Salle Germain, pass the Balcon, and arrive at the river lost since the Tyrolienne.

From here on, the Berger cave becomes more aquatic. The river makes progress difficult.

They make it a few dozen meters more before being pushed back by the narrowing slippery walls and the depth of the water basins, where handlines are needed.

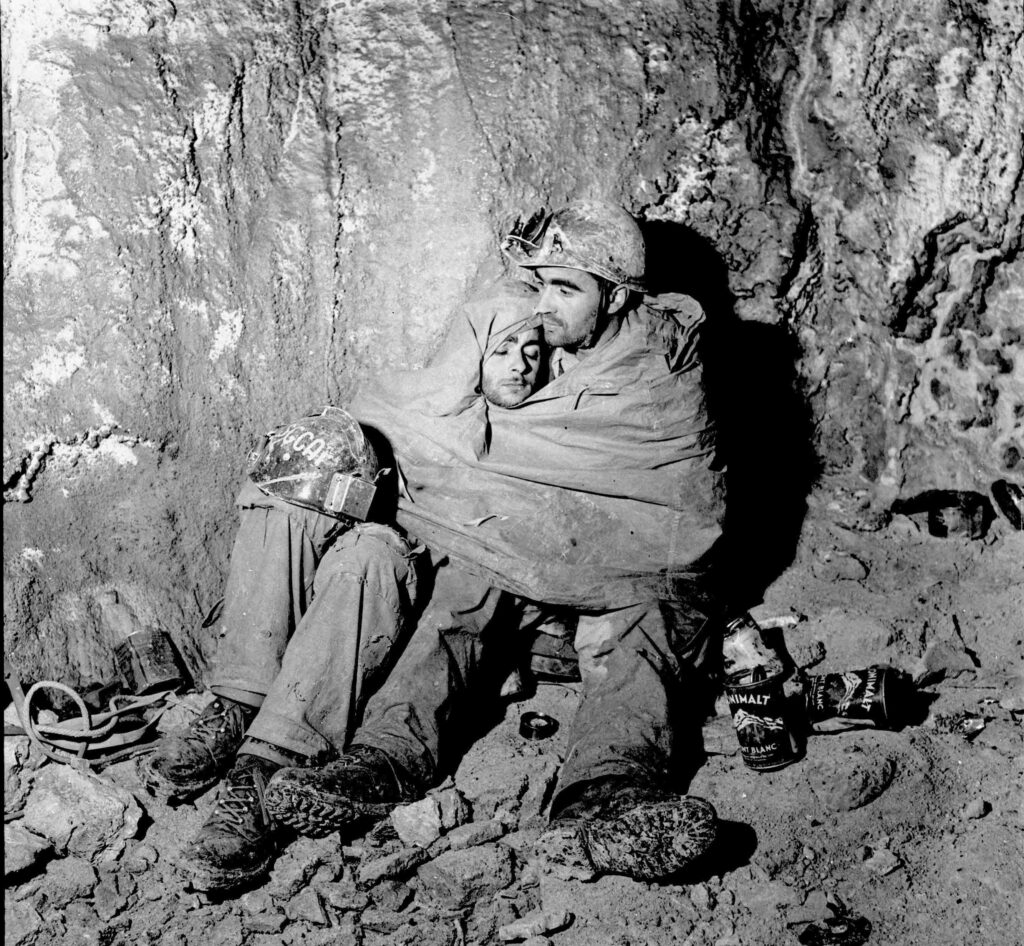

To protect themselves from the cold, they will coat themselves with butter or lard to withstand the 7°C water. Dolpic sessions (a balm to warm muscles) will also be part of the program.

They’ll also be testing aviator suits they’ve bought to go in the water. However, they are soon abandoned, as they tear and take on more water than they protect.

On 26th July, the first team sets off with a canoe, soon followed by a second, but the number of manoeuvres slowed progress too much.

A third team tries unsuccessfully to find a fossil gallery above the meander. The descent along the river continues, uninterrupted by boulders forming dams and waterfalls.

They discover a room with numerous straws on the ceiling. The room is named “Salle des Couffinades” after the straws (fistulas) in the Coufin cave, better known as the Choranche cave.

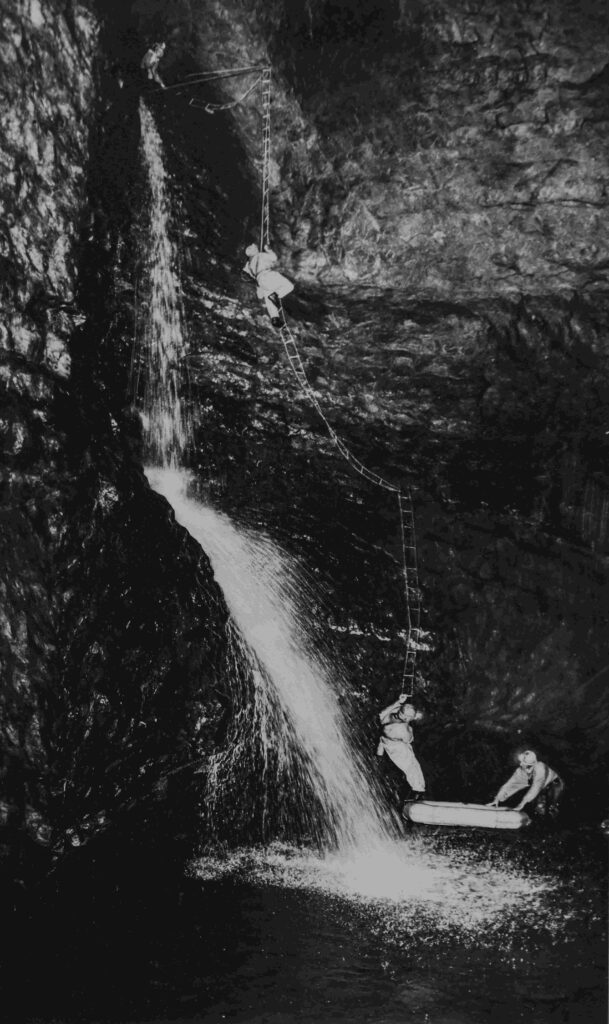

On 27th July, a team set off into the river with the two canoes, but they were stopped by a 17m waterfall (the Cascade Claudine). Brétizel attempted a 7m descent, but was quickly hauled up by his crew after a copious dousing of icy water.

The only way to get down will be to fit it with a guide polemast to get away from the waterfall and avoid being showered by the water.

During this foray in the river, another team tackled the climb opposite the Balcon. Jo Berger passed the ledge, soon followed by Fernand Petzl, but the only find was a crystal room.

The 28th July marks the end of the exploration and the start of the ascent. As the equipment was being carried to the Aldo shaft, some of us took the opportunity to explore the mud gallery at -250m. Progress is not easy, as in places they sink waist deep into very liquid clay.

The whole team will leave with the equipment, tired and exhausted, helped by the support team on 30th July.

The expedition took 142 hours (6 days) and reached -712 m

The team at the exit for this July 1954 expedition.

Standing at rear: Louis Eymas, Pierre Breyton, Jo Berger, Pierre Lafont, Gérard PeaudeCerf, Georges Marry, Claude Arnaud, Claudine Lecomte, Jacques Berthezène, Jacques Aulliac, Pierre Chevalier, Roger Michallet, Marius Gontard.

Seated : Georges Mathieu, Paul Brunel, Louis Potié, Jean et Abelle lavigne, Aldo Sillanoli, Fernand Petzl, Robert Juge.

In August, the decision was taken to carry out another light expedition over a weekend in September, following Fernand Petzl’s workshop manufacture of the mast needed to move the ladders away from the waterfall that had stopped them.

On 10th September, the main team of 7 cavers (Cadoux, Marry, Lavigne, Berger, Mathieu, Garby, Potié) descend to the -500 bivouac.

On 11th September, a team (Cadoux, Garby, Marry and Potié) goes to the Cascade Claudine while Mathieu, Berger and Lavigne wait for them at the Vestiaire. The installation of the mast takes 4 hours, including surface preparation, lead sealing, guy rope/wires, cable clamps and a horizontal ladder to reach the end of the mast.

Georges Garby and Jean Cadoux descend the cascade and advance to a new 5m cascade (named by the topographers).

The gallery continues, but the cascade requires a traverse line and time is running out.

They all climb back up together, leaving the cave rigged for another quick expedition.

Fatigue and cold make the expedition as difficult as ever.

The world record is set at -740 metres.

Press headlines:

“Unknown Sunday cavers have just broken the world depth record over the course of a weekend. At Pierre Saint Martin, they had the help of the army, but at Gouffre Berger, they had no help, no money…

With the equipment still in the cave, they all agreed to do it again on the weekend of 24th to 27th September.

On the 24th, the main team (Sillanoli, Marry, Petzl, Potié, Cadoux, Garby, Brunel, Brétizel) entered the cave in the evening and set up camp at camp 1 at -500m.

On the 25th, the team descended the cascade des topographes and soon descended into the Grand Canyon, with its huge dimensions, steep incline and unstable boulders. The 20m Gaché shaft is descended. It continues over steep slabs to a new shaft where the river rushes down.

Aldo throws a ladder, then Fernand begins the descent, stops and climbs back up. Another pole is needed to clear the cascade and avoid the waterfall. The risk is too great this time.

The ascent took place on 26th September, with a long survey session along the way.

They emerged from the abyss early the next morning, drained but happy.

The world record is easily exceeded at -903 metres with a horizontal development of 2967 m.

Anecdote: Wedding anniversary

Jean Lavigne, whose wedding anniversary is on 27th July, writes a personal message to his wife Abelle, who works as a telephone operator at the surface camp. Jo Mathieu, who has to go up, takes care of the job. However he won’t make it, as the doctor’s laxative jam may be working on him, and in the absence of paper, he’ll have to use it. Scrupulously before use, he memorizes the personal message, which finally arrives safely in another form.

Photos : Collection Jean Lavigne, Jo Berger, Georges Marry